Small Talk 26 - Happiness

For a lot of people, this time of year brings an expectation of profound happiness. Whether the season meets these expectations is another question. Part of the challenge is that happiness is subjective and relative. For some, happiness is an exuberant state of overwhelming joy—a rush of neurochemicals. For others, happiness is closer to a state of calm contentment. It varies by culture; it changes with age.

Happiness is encoded into the American origin story. We are endowed with an unalienable right—not to be happy, but to pursue happiness. This is a funny qualification from the otherwise idealistic Enlightenment thinkers. And since then, the pursuit of happiness has become a multi-billion dollar industry of its own. It's astonishing, the volume of books and websites and classes and podcasts, all promising to help you be happier.

I've been wondering whether happiness is what we might call a solved problem. That is, do we already know the conditions necessary for happiness? Are all the self-help materials just re-packaging fundamental practices humans identified long ago? These questions seem worthy of a little small talk, as the days grow shorter and colder and we prepare for a time of ritual and celebration.

To assist our discussion, I've taken a look at current research and prevailing theories about happiness. There's a lot of it. Perhaps my favorite is summarized in "The Integrated Model of the Determinants of Happiness." In this systematic review, the scholars considered 2,500 peer-reviewed papers on happiness, selected 155 of them, and did some deep analysis. As a result, they conceived of a model for happiness categorized as Health, Hope, and Harmony. I like the consonance, but it doesn't seem very actionable. Nevertheless, it’s a useful summary of what's well-established.

I am led to the hypothesis that we already pretty much know what's necessary to be happy. So, to test this hypothesis, drawing from my research of research, I propose to you these eight actions to create the conditions for happiness in your life.

1. Understand your baseline well-being

Our potential for happiness is bound by some sobering factors, research repeatedly shows. First, your capacity for happiness is at least partly hereditary. If your ancestors were happy, you're more likely to be so. And if not, well, it will be harder. Fortunately, studies suggest that genetics are a smaller factor than others—like, 30% of your happiness quotient comes from genes, they say, with curious mathematical precision.

Secondly, your potential for happiness is limited by your fundamental well-being. It starts with being healthy, safe, and financially secure. People without these conditions can still be happy, but they are exceptional. So, any path toward happiness involves understanding and addressing these baseline conditions. For many, this can be a tremendous challenge, and we should not trivialize it, which is why this action is first.

2. Have a sense of purpose

People who love their jobs tend to be happy because they know what they want to accomplish, they work toward it, and they see incremental progress. A corollary is that people who retire and pursue a life of leisure, without a sense of purpose, are often much more unhappy than they thought they'd be. But purpose isn't necessarily tied to your job. Your sense of purpose can come outside work--from creating art, or philanthropy, or coaching, or spiritual practice. The point is, we humans thrive best when we have something important to do that challenges us.

(A related principle is the idea of flow state, where you concentrate on a task that's just challenging enough. This makes us happy too. It can come from woodworking, or playing piano, or doing a crossword, but flow state often comes from the activities of your life's purpose.)

3. Connect with people

How often do we need to be reminded of the importance of positive human interaction? Every day, probably. And yet we all know how essential it is for us, as social animals. I think one key aspect to recognize is that connecting with people, and maintaining relationships, takes effort. Sometimes a lot of effort, and often when your friends and family don't seem like they're doing their part. But we have to persist, and resist scorekeeping, because that's where happiness lies. Also, research repeatedly shows that in-person time with people (rather than on social media, for example) is much more rewarding and powerful. So even if it makes you anxious, go to where people are, in real life. Make new friends, and keep the old. It's the best.

4. Be kind and generous

We live in a culture where there's a lot of emphasis on thinking about yourself. (Like reading articles about how to make yourself happier.) We also live in a culture—and political climate—that seems to reward cruelty and cold-heartedness. What all this misses is the pure satisfaction that comes from just being kind. There are piles of research to back this up, but I think each of us knows it implicitly. It's just easy to forget. Have you come to know anyone who runs a service for people in need? I have, recently, and while their jobs are unimaginably hard, they glow with a profound state of contentment. That's available to all of us, if we just give a bit of ourselves, and make other people's lives a little better. And if you're in a particularly busy stage of life, you can still pursue this goal, through kind everyday interactions. How powerful it is for someone to remember something about you, or say thank you, or hold the door.

5. Find your system of meaning

Happy people almost always have a personal philosophy, a way of contextualizing life, a method to identify what is good and virtuous. For many people, this comes in the form of organized religion. Others craft a system of meaning on their own, or with like-minded seekers. Regardless, nearly every list of the conditions necessary for happiness includes having meaning in your life. I think it's worth asking ourselves, What's my system of meaning? You may find you lack a satisfying answer. And if so, consider doing a little reading or listening on different philosophies. I'll give you an example. Stoicism, a philosophy developed in ancient Greece and Rome, has had a resurgence in popularity. One concept of stoicism is that you can't typically control the events of the world around you—but you can control how you react to them. Developing the ability to control and shape these reactions leads to equanimity. Isn't that a nice idea? It's the kind of helpful tactic that comes with a system of meaning.

6. Appreciate things

So much of happiness comes from your frame of mind, and by recognizing that you can change your perspective. Appreciation (and its cousin, gratitude) are simple, but powerful, frames of mind. There's a Buddhist thought exercise where you take an everyday object—say, a pencil—and you consider all the people and things involved in its creation. The trees that gave their wood, the architects of pencil factories, the craftspeople, the train that hauled crates of pencils, the train tracks that people laid—it's an almost infinite exercise. But it helps you come to appreciate everything, to know that everything is interesting and miraculous. And this act of appreciation helps create the conditions for happiness, without great expense or stimulation.

An earlier Small Talk discussed training your mind—meditation is a great foundation for increasing your appreciation. So are gratitude journals, or learning to draw or paint, or spending time in nature. (Especially time in nature, according to many studies.) And one more fun data point: Nice things do make us happier. Despite conventional wisdom. Recent inquiries demonstrated that, when people have something they really like, it makes them happier. Not as much as a wonderful experience, but still, happier. Consider the act of taking out a favorite vinyl album and playing it on your turntable. Or the feeling of riding a well-designed bike. These things do make us happier, because they spark our appreciation.

7. Get comfortable with death

I think this is my favorite condition for happiness, because it's the most provocative. How could you possibly get happier thinking about death? Well, it's pretty clear that you can, and you should. Cultures that treat death as a normal thing, and discuss it openly among people of all ages, and conduct rituals that honor death and celebrate a life well-lived—these cultures are, on average, happier.

This is very much related to a system of meaning, of course. Your personal philosophy can help you contextualize your inevitable death. My brother and I have an expression we use when we're doing something a little dangerous. Well brother, we say, it's been a good run. It makes us laugh, but also it suggests that we're content with the life we've lived. It recognizes that when each of us dies, there will be unanswered messages, and an unfinished to-do list, and many persistent problems in the world. Getting comfortable with that is liberating, and a step toward happiness.

8. Don't try to be happy

It's true. People who worry a lot about getting happy, and spend a lot of time pursuing this goal, are typically less happy. Instead, you want to live your life, following the goals listed here, and happiness will come. And when it does, you'll think, Oh, there is happiness. That's nice. And then you'll return to your life.

Well, what do you think? Have we solved happiness? The question is funny, but also hopeful—because then we can move on to the business of living our lives well, which takes a lifetime to master.

Happy Winter Solstice, and all the traditions you enjoy at this time of year.

Have a good one,

Kipling Knox

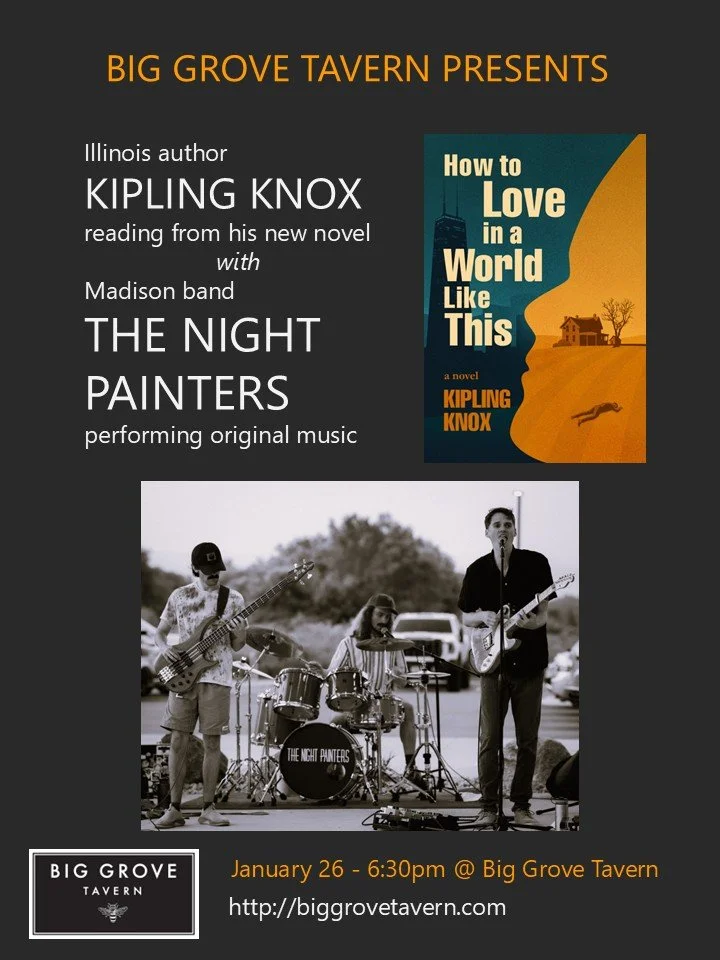

P.S. Don't forget to get a copy of this entertaining, thought-provoking new novel for your holiday reading!