Small Talk 27 - Magnetism

Some days, we need to give our brains a break, living as we do during a time of overwhelming stimuli. Meditation is a great break for your brain, as we discussed in Small Talk 17. But you also might find relief in thinking about physics. The great thing about physics is that its rules and forces are mostly predictable and consistent. The physics working in your body right now is the same as that working at the edge of the Milky Way galaxy, 950,000 light years away. And, as far as we know, the rules of physics are the same all the way to the outer limits of the universe, which is limitless. This is, I think, reassuring. Or at least it puts our human-scale concerns into perspective. So let's talk about one aspect of physics that you can witness quite easily: magnetism.

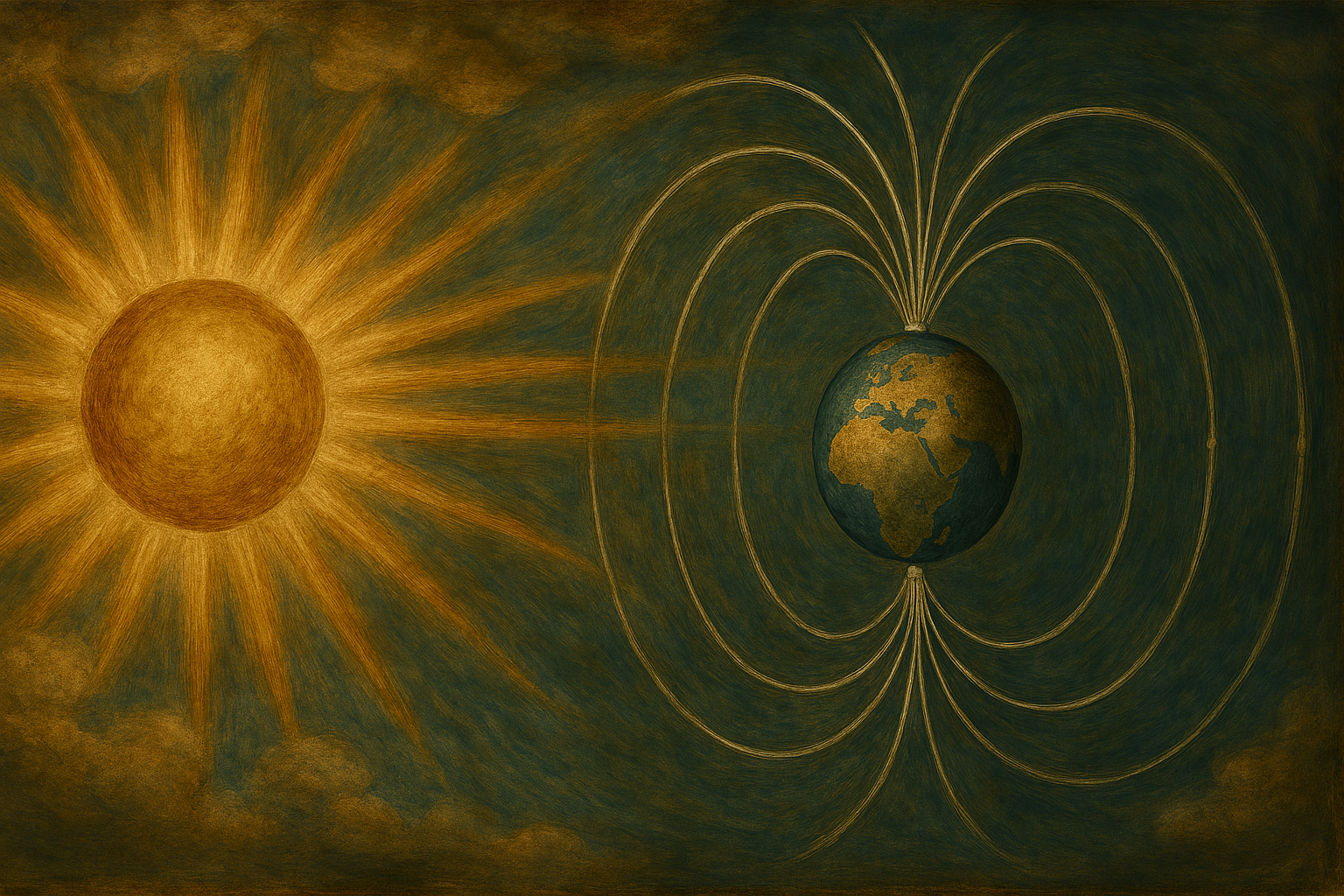

Without magnetism, we wouldn't exist—for many reasons, not the least of which is that magnetism protects life on Earth from the sun's radiation. But magnets are also handy for everyday things. Cordless drills, guitar pickups, fast trains, MRI scanners—they all rely on magnets. We tend to take them for granted, but when we place a magnet on a whiteboard and it sticks, it's kind of magical. And it makes you wonder: how does this work?

Magnetism is one of four fundamental forces in physics. They are: Gravity, the attraction between masses; Strong Nuclear Force, what holds protons and neutrons together; Weak Nuclear Force, which produces radioactive decay; and Magnetism, the interaction of charged particles. That's it—just four. Everything that exists is built upon these fundamental forces. Maybe one day we’ll discover a fifth, but the prevailing model seems to hold up pretty well.

Explaining how magnets work turns out to be quite complicated, but I'm going to try to do it in one sentence. Here it is: Some materials, like iron, have their electrons arranged such that each electron 'spins' in an aligned way, and this alignment produces a charged field of energy that either attracts or repels other materials with an electric charge—this attraction or repulsion is what we call magnetism. Linguists may point out that isn't really one sentence, as it cheats with that dash. And physicists will certainly add nuance, like the notion that electrons don't really 'spin' like a top but instead have a kind of quantum rotation. But among us small-talking friends, that's the gist.

Most materials are not inherently magnetic because the spinning of their electrons is kind of higgledy piggledy. But the neat thing is that you can make some materials magnetic by running an electric current through them. The Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted discovered this around 1820. Let's tip our hats to our Danish brothers and sisters, especially these days.

So, magnetic materials have magnetic fields, which are patterns of energy that flow in a kind of circular way, from one 'pole' of the material (south) to the other pole (north). When opposite poles of magnets get close to one another, their fields flow from one magnet to another, creating a stable loop (or lower energy state, which nature loves) and they are drawn together. It's kind of romantic. When the same poles of magnets get close—like south to south—they are pushed apart. Ain't that just the way.

Earth is one big-assed magnet, with a field that flows between the north and south poles. This is probably thanks to the convection that happens between Earth's liquid iron core and the outer layer of the planet. Once again, it's movement that creates magnetism. So the cause of volcanos and earthquakes is also the cause of Earth's magnetism, more or less. And our great magnetic field deflects radiation from the sun. Without it, the surface of Earth would be more like Mars, which lacks such a magnetic field. When we see the auroras at night, we are witnessing a small amount of solar radiation leaking through our magnetic field.

But there's more! The polarity of Earth switches every 200,000 - 300,000 years. North becomes south in our magnetic field. We know this because there are magnetic traces in the lava that rises under the sea at the mid-Atlantic rift. The rock is kind of striped, magnetically speaking, marking each switch. When this switch happens (which is due fairly soon, apparently), your compass needle will point the opposite direction. Among other things.

If that’s a bit dense, let’s turn our thoughts to birds. Like a lot of animals (bees, whales, salmon), birds are endowed with biomagnetism. That is, they can sense direction from the Earth's magnetic field. Birds use this to navigate when they're migrating. One explanation says that a protein in the bird's eyes is affected by magnetism, and it creates a corresponding blue hue. As the bird turns one way and another, it sees different intensity of this blue, and can chart a course toward the northern climes where it finds a mate and hatches eggs. Research suggests that humans can also detect changes in magnetic fields, but only unconsciously. We also can't fly.

So there you have it. Magnetism. I look forward to corrections from linguists and physicists. But I think the important point is that we live in a world that is so astonishing that we should never be bored. Curiosity, I think, is humanity's second greatest quality. Right after kindness.

Have a good one,

Kipling Knox